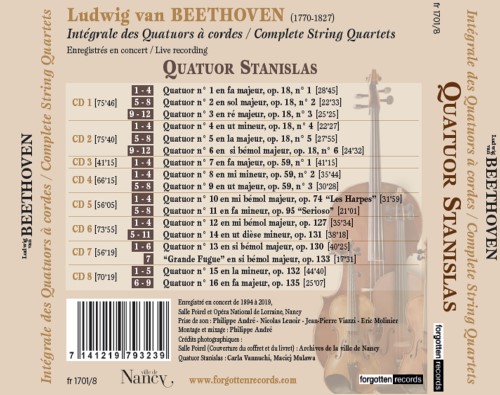

Beethoven’s Quartets – the Complete recording

25 Years in the Life of a String Quartet

Jean de Spengler interviewed by Alexis Galpérine[1]

The Stanislas Quartet celebrated its thirty-fifth anniversary in 2019 …

Yes indeed, about one year after I became principal cellist in 1983, I realized my dream of founding a string quartet with colleagues from the Orchestre Symphonique et Lyrique de Nancy, which has since become the Orchestre de l’Opéra National de Lorraine.

The fact of being members of the same institution has granted a great degree of stability; very few quartets can survive only on their concerts , and countless young groups have been obliged to abandon after a very promising start, because their members became scattered throughout the country in a variety of orchestras or conservatories. While belonging to an orchestra limits the possibility of touring during time off from work, the advantage of having only one schedule to manage allows us to organize steady in-depth work, indispensable to developing a repertory and the style of our quartet over the long run. As early as 1990, we were thus able to offer a subscription season within the Ensemble Stanislas which brought our quartet together with a quintet of wind instruments also from the orchestra, creating a repertory for concerts ranging to octets and even beyond. The season was initially held in the Grands Salons in Nancy’s City Hall and, starting in 1992, in the salle Poirel, a magnificent auditorium built in 1889 with incomparable acoustics.

In this beautiful setting, the Quartet came to build a repertory of several hundreds of works, while recording constantly, to the point of reaching a discography of fifty CDs in 2019. Our work focused on two different things: on the one hand, a rediscovery of lesser-known or unknown French repertory with the world’s first recordings of Guy Ropartz (the complete set of 7 quartets), Jaques-Dalcroze, Maurice Emmanuel, Jean Cartan, Louis Thirion or Henri Sauguet. Recorded after having been played in concert, released for the most part by Timpani, these single-composer albums brought international recognition to these unjustly neglected great musicians.

On the other hand, live recordings during concerts were an objective – from the early 90s almost all the concerts given by the Ensemble Stanislas in the salle Poirel have indeed been recorded in the best of conditions and they make up a collection of several hundred works. Drawing on this collection, Forgotten Records has released over a dozen CDs since 2014, mainly centered on the greats: Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Dvorak, Debussy, Ravel, etc.

Why Beethoven’s Quartets?

Just like Bach’s Six Suites for cellists, Beethoven’s 17 Quartets are the holy grail of quartet players. The most striking thing about these quartets in a repertory so rich in countless masterpieces is that not a single one of them may be considered inferior to the others – they make up a set of 17 absolute treasures! It was a first in the history of music, no other predecessor or successor carried off such a feat. Of course, Beethoven was on the program from the very beginning of the Stanislas Quartet, with Opus 18 no.1 as the opening number of our first concert in Nancy on October 15, 1984. Then, over the next ten years, came Opus 18 no. 4, Opus 59 no. 2, and the 14th Opus 131, which we played quite often in France and abroad. But only in 2006 did we decide to undertake the complete set of quartets split over several seasons, at the rate of three per year, a project we completed at the end of 2012, except for the Great Fugue.

Even though the idea of releasing a discography had never crossed our minds, all the quartets had been carefully recorded by the microphones on a regular basis. It was only in 2018, while I was recording Bach’s Suites for Forgotten Records, that its director, Alain Deguernel, who had happened to have listened to a few of these recordings, said he was interested in releasing the full “live” set. I had my doubts at first, and I carefully listened anew to each of the quartets, whose recordings were spread over about two decades. I was all the more surprised by the impression of a unity behind the performances, augmented by the unity of place (salle Poirel[2]), and the quality of the sound takes carried out by Nicolas Lenoir, then by Philippe André using the same microphones[3].

Quite fortunately, and this was the strongest condition in considering their release, most of the takes had been doubled by recordings of the dress rehearsals, so corrections, minor yet indispensable, were possible – notably the booming fits of coughing right in the middle of a sublime adagio or the driving rain which drenched the salle Poirel one evening in the month of May 2012, making three of six movements of Quartet 13 impossible to use! Besides, the unpredictable aspect of concerts makes them liable to a variety of incidents which may seem innocent but can be unpleasant to hear in a recording, however “live” it may be.

Be that as it may, the goal of the release could not be to approach the technical perfection that only a studio recording can achieve at the risk of being too cold, but rather to attempt to transmit the emotion produced by the concert, including its imperfections.

The Great Fugue, Opus 133 remained. It was initially written by Beethoven as the Finale of Quartet 13, Opus 130 before he was pressured into writing another one by his publisher who was frightened by what was an unidentified object which has remained misunderstood to a great extent until this day. As it was the second Finale that we had played in 2012, we decided to schedule the Great Fugue for May 2019, thereby completing this set of recordings.

Who are the musicians who participated in this collection?

When you consider that 25 years went by between the recording of the fourteenth quartet and that of the Great Fugue, the relative stability of the group Stanislas Quartet over a quarter century may seem surprising – indeed, Laurent Causse (first violin since 1989) and myself (cellist since 1984) participated in the entire project. Since 1986, only two second violins have been replaced: in 2003, Gee Lee, who recorded Quartets 8 and 14, then Bertrand Menut, who did all the others, except Quartets 7 and 13. When he was obliged to stop working for a few months in 2012 for health reasons, he was replaced in those two quartets by Jean-Marie Baudour, who was also a soloist in the Orchestre de l’Opéra de Lorraine. There have also been two violas since 1988: first Paul Fenton, who excelled in that chair until 2007 when the burden of the dual role of violist in the Quartet and solo violist in the orchestra became too much for him. At that point, Marie Triplet, recently name head of the viola class at the Conservatory of Nancy, was called in so that these two excellent musicians could alternate to fill the role of violist in the Stanislas Quartet in the most intelligent manner possible. They have both contributed to half of this collection, making it a true reflection of the life of a string quartet over a quarter of a century, with its twists and turns.

What is your vision of Beethoven’s quartets and is there a school of thought you favor?

These Quartets are habitually split into three groups of periods ranging over thirty years of composition: the six in Opus 18 (1798/1800), the five referred to as “the middle” (1806/1810) and finally the last five Quartets plus the Great Fugue (1825/1827). While Opus 18 may be considered to be a homage to Haydn, the three Quartets in Opus 59 show a clear emancipation from the classic model, whereas the last opuses turn toward a different horizon, leaving their contemporaries behind. Nonetheless, what I find the most striking is that all of Beethoven is already contained in the opening notes of the first quartet of Opus 18 in a single entity with no concessions. Even if he seems to submit to tradition, it is only to demolish it all the better! The most enlightening example is the minuet of which Haydn was so fond, which Beethoven takes and changes into a scherzo, stripping off its old-time “ancient régime” graces with heavy use of accents on unaccented beats and syncopated rhythms. It is easy to detect the rebel trampling good manners. He would not stop surprising his audience, up to the Great Fugue which so frightened his contemporaries. For instance, while most of his slow movements are sublime (the heart-wrenching cavatina in Quartet 13 comes to mind), he deliberately deprives us of this in Opus 18 no.4, in Opus 59 no.3 or in Opus 95.

One permanent feature of Beethoven’s music, however, which must never be neglected by performers is that what is beautiful is never pretty and sentimentality and mannerism are out of place. This necessitates striving for a large, powerful sound without fearing a degree of roughness if warranted for expression.

The uncontested model, for us, is the Budapest String Quartet, whose 1951 recording has aged perfectly. Its great musicians claimed to be taking up the legacy of the Capets who themselves were the inheritors of a line of French quartets who contributed greatly to expanding the notoriety of Beethoven’s last quartets, which were still only played quite rarely in the second half of the nineteenth century.

[1] A violin teacher at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Paris and regular guest of the Ensemble Stanislas since 1988.

[2] With the exception of no. 11, recorded at the Opéra National de Lorraine because the salle Poirel was closed for renovation in 2008.

[3] With the exception of Opus 131, no. 14.