Tribute to George Crumb

on the occasion of his 70th birthday

Nancy - May 1999

In the early 1990s, Laurent Causse, recently appointed first violin of the Stanislas Quartet, introduced us to George Crumb's Black Angels, composed in 1970 and recorded by the famous Kronos Quartet in 1990. We were instantly captivated by this fascinating work inspired by the Vietnam War, which mingled the strange sounds of electrically amplified strings, percussion, voices, a glass harmonica and all sorts of mysterious effects entirely produced by the instrumentalists.

We then decided to measure ourselves against this unknown world, despite countless practical and technical difficulties. The glass harmonica alone was a challenge – but one splendidly met by Laurent Causse and his wife, who went to the Sarreguemines crystalworks armed with a tuning fork to select the twenty crystal glasses of various sizes needed to perform God Music (each one had to emit a precise note). What was probably the first French performance of Black Angels took place in May 1992, during the "Musique-Action" festival staged by the Scène Nationale of Vandœuvre-lès-Nancy. The Stanislas Quartet then played it again several times, including during the "Présences" festival at Radio-France in February 1994, before recording it at Radio-France for Ogam – a label that unfortunately went bankrupt in 2002. In 1996, the Stanislas Ensemble staged a tribute to Henri Dutilleux at the Opéra de Nancy for his eightieth birthday, and it then seemed a fine idea to renew this experience regularly with other great composers. So George Crumb, celebrating his seventieth birthday in 1999, was an obvious candidate. There was an opportunity to see him in the summer of 1998, during the Stanislas Quartet's second tour in the US. Though highly intimidated at the thought of meeting such a famous figure in American music, I phoned him, and he immediately invited me to his home in the suburbs of Philadelphia. At the address he had indicated, I saw a gardener in shorts pruning roses, and asked him where Mr. Crumb's house was. He turned around and beamed at me: it was the master himself!

Astoundingly, he immediately accepted our invitation, as though the idea of coming to Nancy were as natural as responding to an invitation from the New York Philharmonic, which had just devoted an entire retrospective to him. However, I should mention that the initial event with Dutilleux in 1996 had been considerably expanded: it now involved the Nancy Symphony Orchestra, the "Musique-Action" festival and the Nancy Conservatoire during a week of concerts, get-togethers and master classes, between 3 and 7 May 1999.

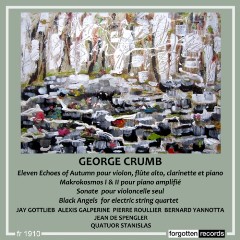

I have very fond memories of the concert on 4 May, when some of the works on this CD were performed: Eleven Echoes of Autumn, Makrokosmos for piano and an early work, the Sonata for solo cello (1955). He came to the rehearsal, and when I asked him if he had any criticism or comments, he replied with a broad smile: "No, no, it's very good. But you know, I feel like I'm hearing someone else's work: maybe a quarter of it is Boris Blacher (his teacher in Berlin), a quarter of it is Bartók, a quarter of it is Hindemith, and only the last quarter of it is really me!" But in fact, this is a really magnificent piece, which has been adopted by cellists around the world.

One of the highlights of the week was the concert on 6 May for the reopening of the completely renovated Salle Poirel, which featured the first French performance of A Haunted Landscape for orchestra, conducted by Mark Foster, along with Four Nocturnes for violin and piano, and Black Angels. In these works, the composer was far more articulate than in the Sonata for cello, as they expressed his fully mature style. I remember that after an early performance of the orchestral piece, he jumped on stage and dived under the piano lid to show the astonished pianist how the "prepared piano" effects (one of his great discoveries) should sound. He looked just like a mechanic under the hood of a car – and in fact, he refers to himself a sound mechanic. I would personally call him a poet of sound, but it just shows what an extremely modest man he is.

Jean de Spengler

It goes without saying that the actual presence of the composer gave these "Rencontres George Crumb" meetings a particular aura, solemnity and sense of commitment inspiring everyone to rise to the occasion. So all the instrumentalists have their own treasured and sometimes moving memories of the fascinating hours experienced with him during rehearsals, shared meals and walks around the city – decided bonuses on top of the concerts.

George Crumb did not hide his delight at being celebrated in this way in a beautiful province of France he had never visited before, nor his satisfaction at the care given to every performance of his works: all marks of respect for him. Endless funny and touching images are etched in the memory. For instance, I remember him rubbing the piano strings with my rosin block in search of a sound effect he never tired of exploring, like the brilliant tinkerer he was. (He completely destroyed the rosin, for which he was deeply apologetic!)

Another memory: during a France-Culture broadcast, when, assailed by a learned musicologist asking searching questions about various subtle aspects of his writing, he answered blandly, with a mischievous grin: "Oh, you know, I wrote that while thinking about the river at the bottom of the garden in my childhood home..." He seemed to relish playing the West Virginia farmer to the hilt: a vision shored up by the blue jeans and thick checked shirt he nearly always wore. The curious were met by naïveté, both feigned and genuine, profound knowledge and disarmingly simple manners. So this exquisite man, this great American, this true poet of sound, managed to preserve his share of mystery, refusing to separate candour and complex thinking, as though keen to preclude any excessive analysis, and leave all the questions raised the world over by his ever-inspired music hanging eternally in the air.

Alexis Galperine

English translation: Theresa Lister