MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL ( July 2020)

When Louis Thirion was forty – the age when most composers have found their personal and unique voice, and are reaching their creative peak and maturity – tragic personal circumstances made him abandon composition and devote the rest of his life to teaching. He hailed from Baccarat, a small city in north-eastern France, famous for its crystal making. He learned his trade from Guy Ropartz, who taught him composition at Nancy Conservatory. In 1898, he was appointed Professor of Organ and Piano there. His career stalled when war broke out, and he embarked on a period of military service. In 1920 his wife died, and he was left single-handed to raise two young children. This led him to turn his back on composition, and thus the world was deprived of a fine composer. He lived until his mid-eighties.

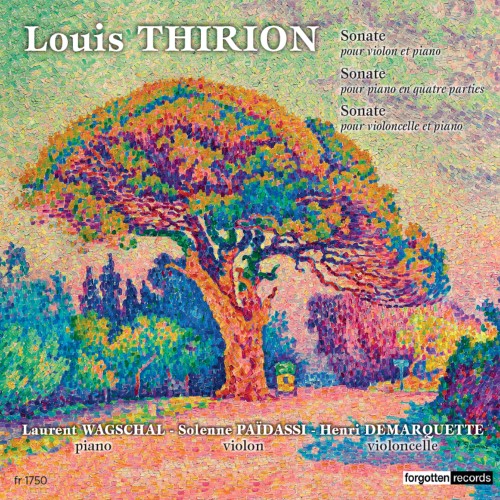

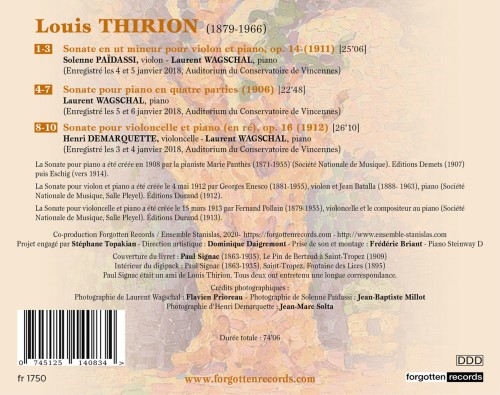

The three chamber works featured here span seven years from 1906 until 1912, a period of intense inspirational creativity. The earliest work is the four-movement Piano Sonata, written in 1906, dedicated to Guy Ropartz and premiered in 1908 by Marie Panthès. Although I have not seen the score, I can only assume that it demands a commanding technique. Laurent Wagschall rises to the challenge admirably. The mood of the first movement is serious and shot through with impassioned intensity. There follows a scherzo-like movement, whose rhythmic ambiguity, where a motif which spans three beats is arranged in four-beat measures, gives a sense of uneasy forward momentum. The slow movement, marked Lent, reveals the composer’s melodic gifts. The relentless accompaniment confers an element of mystery over the landscape. The Sonata’s finale fuses energy with Lisztian bravura, ending the work with all guns blazing.

The Sonata for Violin and Piano was composed in 1911, and premiered in May the following year by George Enescu and Jean Batalla at the Société Nationale de Musique, an organisation dedicated to promoting the work of young French composers. It is set in three movements. The first draws back the curtain on sweeping romanticism, ardent and yearning, yet confident and life-affirming. The middle movement is in three sections. It opens with a tender mix of wistful lyricism and consoling embrace. Then, responding to more pressing ambitions, it veers off and struts a more keen gait. Towards the end, it returns to soothing melodiousness. The finale is optimistic, confident and contented; the piano part is quite virtuosic. Païdassi and Wagschal play with utter commitment, injecting plenty of personality into their playing.

A year later came the Sonata for Cello and Piano, which bears a dedication to Fernand Pollain, who debuted the work in Paris in March 1913 with Thirion at the piano. Once again, the concert was hosted by the Société Nationale de Musique. The long-spun doleful strains of the cello, accompanied by a delicate arabesque-like accompaniment, usher in the opening movement. Midway comes a meditative section, before a high-spirited conclusion. The middle movement is one of melancholic resignation. Glistening ripples on the piano, accompany the cello's Lent opening in the third movement. Eventually the sun breaks out, and the mood becomes more upbeat and genial. Both players perform with infectious zeal and enthusiasm.

The performances are warmly recorded. The booklet notes, in French and English, are packed with biographical information and analysis of the works. For those keen to explore, please do not hesitate, as there is much to simultaneously interest and stimulate. For the enthusiasts: I have previously reviewed a disc of Thirion’s chamber music and a recording of his Second Symphony. Both are rewarding.

Stephen Greenbank