Interview with Jean de Spengler, founder of the Ensemble Stanislas

by Alexis Galpérine

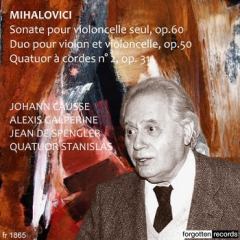

Alexis Galpérine: As part of the season of concerts given by the Ensemble Stanislas in Nancy, you wanted to pay tribute to Marcel Mihalovici, a man you and I both knew, and who, like many other 20th century composers, has been pretty much forgotten.

Jean de Spengler: Yes, it surprises and saddens me that there are so few recordings of his music around today.

AG: It's a limbo that has also engulfed his colleagues from the Paris School, with the possible exception of Martinů. Alongside Bohuslav Martinů, Alexander Tansman, Tibor Harsányi, Conrad Beck and Alexander Tcherepnin were a group of foreigners who moved to France in the inter-war period, and were later joined by Igor Markovich and Alexander Spitzmüller. As far as I know, they were given this name by the critics, echoing the Paris School of painters.

JS: This cosmopolitanism was certainly at the root of their originality (they came from Russia, Poland, Switzerland, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Romania), and was also a way for them to merge their original cultures into the hotbed of influences embodied by Paris in the first part of the century. Mihalovici, who arrived from Bucharest in 1919 at the age of twenty, was totally representative of this twofold allegiance, through his militant temperament, which proclaimed his birth in the phenomenally creative environment of Mittel Europa, and his seamless integration into French culture. As we know, he was friends with Vladimir Jankélévitch, Pierre-Jean Jouve and Samuel Beckett.

AG: And here we think of Enesco, his lifelong mentor and friend, who was also intimately attached to his native land, but deeply French as well. It's true that Romanians have always felt at home in Paris: you don't need to have read Cioran or Ionesco or attended Celibidache's concerts and talks to know that...

JS: His link with Enesco was clear, and undeniably important.

AG: It went back to his childhood: Mihalovici's violin teacher, Bernard Bernseld, was himself one of Enesco's pupils, so it was easy for Bernseld to introduce his young protégé to his teacher. All the musicians of the Austro-Hungarian Empire – as we know – were well-versed in writing for strings, but Mihalovici's exceptional mastery in this field stemmed from a quasi-identification with his model...

JS: Mastery in terms of writing, of course, but there was also a singular love, which you sense right from the very first bars of the works presented here. In the violin-cello duet, the second quartet and the sonata for solo cello alike, the meld of both sides of the same coin is striking – two aspects intrinsic to the very history of the string family: the folk vein (that of village instruments) and a unique role in the development of the great classical forms. So it's not surprising that melodic and rhythmic Romanian motifs suddenly appear in an otherwise highly structured discourse that constantly harks back to Bach.

AG: One thing stands out for me: Mihalovici greatly admired Max Reger, the uncontested champion of what was disparagingly called "fake Bach", especially in his solo works for violin, viola and cello. It must be said that this admiration was not exactly prevalent in France at the time...

JS: To say the least! However, this obsession with form is mainly found in the example of Vincent d'Indy, who himself revisited older forms from the classical and pre-classical periods in his late works, in his own way.

AG: It's true that Mihalovici, like Martinů, came from the formidable melting pot of the Schola Cantorum: a "temple of conservatism" that always attracted modernist musicians from Albeniz to Varèse and from Satie to Roussel, to name but a few.

JS: It's so important not to pigeon-hole people.

AG: The cello sonata, with its deliberately neo-classical style, was written in 1949 for André Huguelin, and created by André-Lévy: a marvellous man, who was your first teacher.

JS: Yes, a great musician whom I loved very much. It was through him that I met Mihalovici.

AG: André-Lévy was also a friend of the violinist Marie-Thérèse Ibos, one of my teachers, and I remember that we worked on Mihalovici's duet from the original score, meticulously fine-tuned under the composer's supervision. She played this work several times, with André-Lévy and Reine Flachot.

JS: In this piece, the rhapsodic vein takes precedence over the Constructivist spirit. By the creator's own admission, it draws directly from Enesco's great example. However, the refined balance of colours is clearly nourished by the French spirit.

AG: Can you tell us a little about the second quartet?

JS: It was created in 1931 by the Roth Quartet. This is what Gérald Hugon said about it:

"This magnificent work illustrates the composer's contrapuntal genius, which enables each instrument to flourish in all its individuality. Two substantial, solidly constructed sonata-form movements, the last with a dance-like ambiance, frame a short, intensely expressive "aria" section. The harmony sometimes borders on atonality through the intensive use of chromaticism, but is always underpinned by a tonal centre. This work is a synthesis of traditions: French in its refined sonorities; Romanian in its spiritual link with the music of Enesco; German in its contrapuntal writing and consummate conception of great forms, in a direct line from Beethoven, Brahms and above all Max Reger, whom Mihalovici admired so much. I find the strength, starkness and tension of this quartet fascinating."

AG: We should now talk about the man we were lucky enough to meet, especially when we played in a trio with Josette Morata, a student of his wife, the great pianist Monique Haas. Our musical environment as young musicians was coloured by those close to the Paris School: André-Lévy, Marie-Thérèse Ibos (who gave the first performances of works by Tansman, Tcherepnin, Beck and others) and Ina Marika, Monique Haas' assistant at the Paris Conservatory and a friend of Martinů's and Harsányi's. This was in the 1970s, and I particularly remember a concert at the Centre Rachi in Paris, given in support of Anatoly Shcharansky and the Jews of the USSR. Jankélévitch presented the evening. I played with Josette Morata, and Monique Haas performed a few pieces by Chopin and Ravel. That was when I saw Mihalovici for the first time, and was deeply impressed by his simultaneous power and gentleness.

JS: Without losing any of his Central European charm, he also embodied that street urchin spirit of the first half of the 20th century, as we can see in the incredibly funny letters he wrote to his friend Henri Dutilleux (Henri Dutilleux, by Pierre Gervasoni/Actes Sud). Incidentally, his friends called him Chip! In the 1970s, when I had the pleasure of meeting him through my dear André-Lévy, he was living with his wife Monique Haas in a tiny apartment in Rue du Dragon, in the Latin Quarter. It was a complete shambles, where the walls seemed to consist entirely of books and scores piled on top of each other, and the piano took up almost all the remaining space. So they took us to a small Italian restaurant in Rue des Canettes, which they used as their canteen. And there, what a delight it was to listen to him telling endless stories – in his marvellous French tinged with Mittel Europa – about the Paris of the inter-war period, and his encounters with musicians like Enesco, Martinů, Vincent d'Indy, Bartók and Ravel, and with painters, poets and writers from all over the world. All these people lived in the streets of the Latin Quarter and would meet up in the evenings in the main cafés of Montparnasse, like La Coupole and La Rotonde.

English translation: Theresa Lister